Dave Calendine’s mind raced through his options as his introduction neared.

He had fans to entertain and minutes to fill in Comerica Park’s pregame festivities on May 10, 2024. The announcers on screen compared the Detroit Tigers’ uphill season to Rocky Balboa’s underdog journey, and Calendine had his inspiration. When the camera panned to Calendine’s four keyboards, 244 keys and two computer monitors, the celebrated Detroit organist jammed out the Rocky theme “Gonna Fly Now.”

The familiar tones of a theater organ—Calendine’s own that the team bought off him—filled the downtown ballpark. Tiger fans rejoiced. For the first time in Comerica Park’s 24 years, the Tigers had a live organist.

“The response by the crowd was just mind-blowing,” Calendine said.

By the seventh inning stretch, fans had pinpointed the organ’s perch and lauded Calendine during “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

“People turned around and faced the press box,” Calendine said. “Never expected that. Never expected to have it for the first time be so well received.”

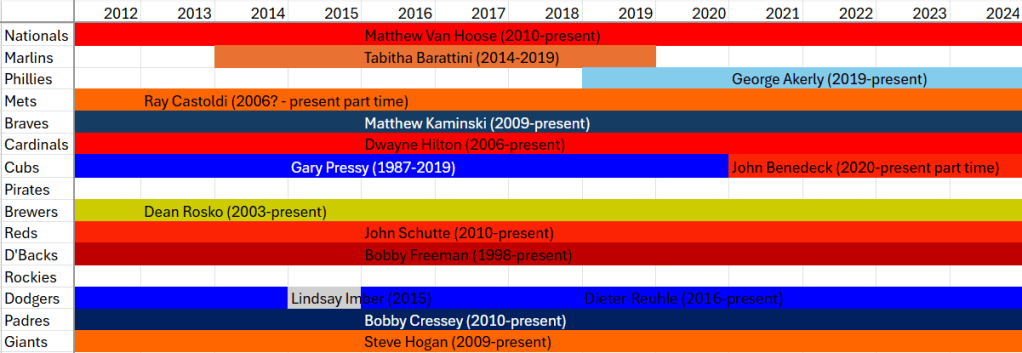

Though the world has gone digital, baseball’s organists have thrived. Seventeen of Major League Baseball’s 30 ballparks enjoyed live organists in 2024—among the highest figures ever.

In a spirited game ripe with tradition, the storied instrument fittingly underscores stages that revere sacred customs and beget new dramas.

There’s something about Chicago

The sports organ laid its roots on the banks of Lake Michigan.

In 1929, Paddy Harmon, a magnanimous Irish-American businessman, installed a massive pipe organ in Chicago Stadium, which boasted “the roar of Niagara and the modulation of whispering angel voices,” according to a Bartola Musical Instrument Co. advertisement.

Harmon specifically sought Bartola’s services for the custom instrument to fill the cavernous, 25,000-seat arena, which resembled more a train station or aircraft hangar than a traditional hockey and basketball arena.

The Chicago Tribune’s Blair Kaiman likened the hall to a temple and shrine, pointing to the organ’s “loft, dead center behind the basket or the hockey goal, as if it were in church.”

Not wanting to play second…well…organ, team owners nationwide installed (mostly electric) keyboards in their own arenas in the 1930s.

Exactly why Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley decided baseball should be the organ’s next realm in 1941 remains nebulous. Perhaps organist Ray Nelson was a friend. Perhaps General Manager Jim Gallagher convinced him Wrigley Field pageantry needed spicing up.

Paul M. Angle wrote in “Philip K. Wrigley: A Memoir of a Modest Man,” that organist Nelson “startled the fans” with his first notes. Sporting News complemented the organ’s welcome place alongside other sensual delights like ballpark franks and beer.

Though well-received, the instrument was short-lived. The Tribune reported Nelson had to “still his bellows” in his April 26 debut because the Cubs’ radio broadcast lacked permission to air certain melodies. By Chicago’s next homestand, the organ was a memory.

The Cubs waited until 1967 to employ a full-time organist at the friendly confines.

Gladys Goodding became the sport’s first full-time organist when the Brookyln Dodgers hired her in 1942. Goodding played until the Dodgers’ New York departure in 1957 and is the first in an extensive line of celebrated women baseball organists.

ORGANIST SPOTLIGHT: Gladys Goodding, the first woman baseball organist, is the answer to the kitschy trivia question: “Who is the only person to play for the Dodgers, Knicks and Rangers?” She famously received criticism over playing “Three Blind Mice” in response to a questionable umpiring decision.

The St. Louis Cardinals hired Audrie Garagiola, wife of Cardinals player and broadcaster Joe Garagiola, in 1955. Helen Dell played at Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium from 1972-1987.

ORGANIST SPOTLIGHT: Audrie and Joe Garagiola married in 1949. In 1966, Busch Stadium hosted the MLB All-Star Game, in which Audrie provided organ music. “I played nine years in the big leagues and my wife plays in an All-Star Game before I do,” Joe lamented.

Back in the Windy City, the White Sox employed Nancy Faust from 1970-2010, and since then have enjoyed Lori Moreland at the keys, which makes 55 consecutive years of a woman in the role. The White Sox did not respond to an interview request.

One of baseball’s youngest organists, John Benedeck, 30, plays at Wrigley Field and Omaha, Nebraska’s College World Series. In May 2020, with baseball on hold, Benedeck filled the Wrigleyville air with an hour-long concert, delighting passersby to a moment of levity during a dismal pandemic.

Whether Harmon and Wrigley realized or not, their organ innovation appropriately celebrated Chicago’s reputation as not only a basin of boisterous music and sport, but a funnel for literal wind, which blows over the Great Lakes and midwestern plains and into the pipes of the beloved instrument.

Click each team logo for a video on the organist

A Solo Orchestra

Wind is the driving force behind organ music.

Air thrust through larger and smaller diameters creates the tapestry of sounds, which animate the bevy of pipes you might see in a traditional instrument.

“If we were back in the medieval times, then it would be a couple of organ boys who were up in the back in the chamber,” said Tim Plimpton, a church organist in Delaware. “And they would be working their tails off to pump these giant bellows to create the air pressure into that pipe chamber.”

Today, an inexpensive motor provides even more air pressure than medieval child labor. As air passes from the chamber to the organ’s pipe manifold, a series of stops blocks airflow to most pipes while allowing it to blast through specific pipes selected by the player’s keystrokes.

While the organ’s range and symphonic tones are impressive, “it’s actually more remarkable that all of the keys are or all of the pipes are being silenced at the same time,” Plimpton said.

Cathedral pipe organs, though appearing luddite vestiges to a timeless tradition, now use electro-pneumatic relays to signal the organist’s strokes. Keystrokes inflate switches, which connect to a relay panel.

Calendine plays a pipe organ at Detroit’s Fox Theater—one of his primary venues alongside Comerica Park and Little Caesar’s Arena, for Red Wings hockey games.

His sports organs are digital, “but everything is recorded from a real theater pipe organ and stored as a digital sample,” he said.

Be it a theater, a church or a ballpark, the organ’s sustained airflow allows the instrument to lead the most raucous of venues.

“The sustain of the organ is what keeps the music from getting totally swallowed up by the crowd,” Plimpton said.

As the organist stacks and layers tones, melodies and rhythms, he or she assumes the role of a conductor, orchestrating a one-person symphony that eclipses solo performance, mimics an orchestra and draws the throngs of faithful fans into jubilant harmony.

“It’s like the perfect merging of what a conductor of an orchestra does, because they’re corralling all of these individual sounds being made by this huge number of individuals,” Plimpton said, “bringing that all together into one place.”

‘Call and response’

Dwayne Hilton sits in the “central brain” of entertainment at Busch Stadium—a glass-enclosed organ room next to the public address announcer and audio mixer. The St. Louis Cardinals’ organist is entering his 20th season in the booth, platooning organ time with Jeremy Boyer.

His first prolonged performance comes during the ceremonial first pitch.

“Baseball is everything from kids to 90 to 100-year-olds,” Hilton said, so he plays decades music from the big band era through classic rock and pop.

“I’ll pull off a Taylor Swift song or just something goofy so the young kids would be like ‘ah, he’s playing it on the organ.’”

During gameplay, Hilton attends to every pitch, playing at all the right moments and none of the wrong ones. MLB requires all music to stop when the batter is in the batter’s box and the pitcher is touching the rubber.

In the top of each inning, Hilton “stings the outs,” playing a quick note or two after a defensive success. In the bottom half, he plays “the fun ballpark stuff.”

“Charge” and “The William Tell Overture” are fan favorites.

“When we got a runner in scoring position, I’m really paying attention to that,” Hilton said. “Because now I’m going to make it even more exciting and create a little bit more tension to get people in the game.”

Organist Spotlight: Hilton succeeded the legendary career of Ernie Hays, who played from 1971-2010. “A Jedi of organ,” per Hilton, Hays pioneered walk-up music for batters and relief pitchers, according to his 2012 obituary by the Associated Press.

Hilton’s position in the mezzanine press box is typical, and ideal, for organists. Jack Henriquez, who played for the Tampa Bay Rays at Tropicana Field, sat in centerfield near the camera well.

“It’s kind of hard because you’re hundreds of yards away from the [batter],” Henriquez said. “But you have the director in your ear telling you, ‘go ahead.’”

While the organ in St. Louis has thrived since the 1950s, a handful of teams have shied away from the instrument. Henriquez landed in the hospital in 2019, and the Rays have not employed a full-time organist since. The Texas Rangers dropped their organist after their 2023 World Series championship, and the Miami Marlins have not employed one since the pandemic.

For teams like the Cardinals, with a tradition-steeped baseball history, the organ is as integral to the ballpark as peanuts and the foul poles.

“I think if we took that out, we might actually get some angry emails,” said Jared Haukap, the Cardinals’ manager of scoreboard operations and game presentation.

Haukap is one of the voices in Hilton’s ear at Busch Stadium, directing much of the audio and visual presentation.

At the end of the seventh inning each game, Hilton plays the Budweiser song, “Here Comes the King,” which coincides with the last call for alcohol sales. On Opening Day, playoff games and other special occasions, the Budweiser Clydesdales march on the field to the tune.

“Dwayne may end up playing the ‘Here Comes the King’ song eight times in a row because that’s how long it takes the Clydesdales and the cars with the Hall of Famers to go around the warning track,” Haukap said.

Understandably, Hilton knows “Here Comes the King” like it’s “Hot Cross Buns.” Other tunes he plays by ear, as did Henriquez at Tropicana Field. Spontaneity gives the organists the latitude to musically respond to the game’s unpredictability and appeal to the crowd.

“What’s the crowd doing? How can I play to keep it going?” Hilton said.

Busch Stadium becomes his personal orchestra’s 40,000-person choir. Hilton plays the prompts; the crowd responds.

The call and response exchange at the ballpark mirrors the organ’s other home. Church.

A Transcendent Sound

The reason organs enliven the atmosphere at Wrigley Field and Busch Stadium is the same reason cathedrals, crafted with fine materials and illuminating art, boast organs as well.

“When you find something that’s built reflective of love, you always find beautiful details in it,” said Fr. James Hudgins, a Catholic pastor and church architecture expert.

The word “holy” means “set apart,” and holy buildings should reflect the revered activities they host. One reason the Oakland Coliseum met its demise, according to Hudgins, is that it sacrificed “the spirit of football to the spirit of baseball,” and vice versa. Notably, the Athletics did not have an organ.

Meanwhile, ballparks like Fenway Park and Wrigley Field live on a century after construction, packed with choirs of fervent fans calling and responding with the organ in celebration of a shared love for baseball.

“I love playing organ, and I love playing organ for church,” Hilton said. “I do get that same response…They’re reacting, they’re responding, hopefully in a spiritual way, hopefully they’re connecting with [the divine.]”

“It is this mutual exchange that happens,” said Fr. Luke Melcher, a Catholic priest who holds a master’s degree in liturgical music.

“The organ itself has this capacity to help us breathe and to carry the melody itself, carrying us into the celestial realm.”

In the beginning, Genesis says, “a mighty wind swept over the waters.” Wind, throughout scripture, symbolizes the spirit breathing life into creation. In the same way, the hollow, breathiness of an organ note evokes a historic spirit of a religion—or a game—celebrated today.

“The word tradition in Latin comes from the word traditio, which means to be handed on,” said Melcher.

“There are things about life that require a wisdom that is not something that is immediately picked up on the side of the street, you have to receive it.”

Henriquez shared a similar sentiment about the organ at Tropicana Field.

“It’s so romantic when you walk in,” Henriquez said. “Baseball is a handed-down thing. You know, your grandpa handed it down to your father and he handed it down to you and brought you to the park.”

Yet the organ’s buzz and sustainment account for the demand of present action, urging reactions from modern supporters.

Josh Noem, an editorial director at Catholic publisher Ave Maria Press, earned notoriety on social media in 2018 when he likened an image of Cubs rookie David Bote rounding third on a walk-off home run to entering heaven. Jubilant fans sang with arms outstretched like choirs of angels waiting for a hero at the gates.

“You’ve left home and then you’re coming back, and you’ve got all your teammates there waiting for you,” Noem said. “And it just struck me as this perfect image of heaven.”

Baseball, of course, is not church, but the fervor and diligence of its patrons reflect the same human thirst.

“Great architecture in both churches and in stadiums do that really well, to give a sense of the transcendent and eternal,” Noem said. “But in a way that’s very rooted in the particular experiences of the places where they’re located.”

The Finishing Touches

In December 2024, Paris rededicated Notre-Dame Cathedral after its restoration following the 2019 fire. Church figures and world leaders gathered in France’s beloved sanctuary for a Mass. The archbishop sang to the organ, “wake up,” and the organist responded with a deep, but light fanfare mimicking the call before bursting into full chords.

“In the French literature, that improvisation is a big thing for them,” Calendine said.

Both church and ballpark organists utilize improvisation practically to seal gaps in the action and philosophically to draw the participants’ attention to a spiritual realm.

“The idea of improvisation is to extend the same melody throughout the time and let it linger,” Melcher said.

Improvisation, in church and baseball, is a mark of the living, breathing person commanding the music.

“The skills of artists and artisans and musicians are the highest expressions that we have,” Melcher said.

On Opening Day 2025, the beloved baseball tangibles will delight again—the green grass, the boiling peanuts, the cold Budweiser. And in most stadiums, fans’ ears will relish in, as The Sporting News wrote in 1941, the “restful, dulcet tones” of a ballpark organ.

The purpose of a ballpark is to host a baseball game. But inasmuch as baseball players’ athletic prowess celebrates human excellence, organ music lifts the human soul and heightens the experience in a different, but tangible realm.

Without an organ, the game or the liturgy can still go on. Though, Melcher said, “the organ itself has such a particular capacity to help us pray and sing that one does wonder if it is almost necessary.”